The prevailing notions that have been the foundation the last ten years of my professional life are: #1 working for yourself is great, #2 that technology allows for telecommuting so that you can easily live in one locale and work in another, and #3 doing what you love will give you a happy life.

After ten visceral years of living this experience to my fullest capabilities, I have removed all the vague but powerful impulses that have led me down this road, and I am able to isolate and identify these grand assumptions. With many experiences behind me, I am now able to learn from my own history, and correct it so that I might better myself as I continue through life.

CORRECTION #3: doing what you love for who you love will give you a happy life.

There is an old adage attributed to Confucius that says, “Choose a job you love, and you will never work a day in your life.” My teachers, guidance counselors, and career advisors from elementary school to graduate school have perpetuated this message. “Just discover what it is you love and with hard work, a career can be made from it.”

I have lived by this belief and discovered it is only half true. For more than ten years I have had a successful career as a graphic designer. I have a broad technical skill set as far graphic designers go, and it continues to grow. I’ve had commercial and critical success exclusively as a photographer when I’ve applied the effort in my adult life, with several exhibitions, and lots of national magazines, newspaper, books and websites publishing my images – even some years teaching the subject at the college level.

My correction is not because of a lack of success in my career, but perhaps more importantly, my career’s lack of satisfaction in my life. This feeling may be surprising to many who see my choice of livelihood as one that seems exciting, gratifying, and to some, even envious.

The problem with this position is like so much else; we lack the intellectual rigor to see this notion fully through, or to take agency and the risk in making the proverbial break for ourselves, so that we may see over the hilltop of our own wistful notions. After 10 years of wrestling my interests and passions onto their backs and slapping the mat for a paycheck, I now have a correction to make for myself, so that I may better navigate my road ahead.

Your money is not equal to my love. It can’t be. It shouldn’t be.

This correction is not a complaint. I understand my path–one that trades my personal ideas and experiences for monetary value–is a steep one. Stable income is nearly nonexistent when working for myself as I have. In any creative service based endeavor, instability is always a concern and the consequences can be stark and chronic. When inspiration and optimism get scarce, I know that it always gets harder. I know that business is not fair, that compensation is not commensurate with talent nor effort. I know I cannot trust anyone at their word until the check has cleared and that pats on the back don’t buy groceries. I know that skill and intelligence bear little factor in opportunity, especially in the creative fields. I am making this correction for a more fundamentally reason: to pull the veil away from the belief that doing what I inherently enjoy for a fair transaction for someone else’s very passionless cash is a busted myth. It is bad math; the two are incompatible currencies. I am writing to critique the translation between my love and other people’s money.

Empirical evidence has offered me this correction: to follow what I love, and expect to get paid for performing and producing it is both vain, and in vain. It is naive and ignorant at best, selfish and narcissist at worst. To do what you love for others, and expect to get paid what you are worth in money is a flawed transaction from the start. Why? People don’t love or understand what I do nearly as much as I do. They couldn’t. To think they do is ignorant. To expect others to reflect the same amount of satisfaction, appreciation, and value as I of my work is egotistical. To expect others to feel the same and reciprocate in equivalent cash value is naive. Yes, I do get paid, but when the costs, time, and energy are tallied for the work I do, it is seldom a fair trade for the money because money cannot measure or reimburse all aspects of the creative process. The truth that has taken me a long to discover is this: nobody pays for love. They only pay me for the megabytes it yields.

What I do is fun because I am told it is fun

Where does this assumption and expectation come from? The notion that it is possible, even our right, to turn what you love to do into a career is often exacerbated by the messages in popular entertainment and American post-secondary education. I have experience in both, and on this topic, the similarities among the two are often upsetting. Both of these industries are for profit, though one more blithe than the other. And selling dreams, namely the American Dream, has always been good business.

Time and time again, new acquaintances express passing envy that I “get to do what I enjoy” for a living. My recent impulse is to reply in part jest, “I never said I enjoy commercial art, or taking photographs, or designing websites.” It is a job like most anything else. It’s not always easy and it is not usually fun. But before I get on my stump and try to explain this to the next poor guy who wants to pay me a compliment, I should try to understand this perspective better.

Somehow, someway, being a designer (or a photographer, or any job in commercial art and design) has been judged in our culture to be more a recreational activity than a profession. While most of us are both amateur plumbers as well as photographers on some days, it’s the photography we prefer to lament. As far as I can tell, this perspective exists simply because the profession has been oversold. Again, this is explicit in popular entertainment. Perhaps more pervasive it is explicit and almost universal in today’s art school recruitment advertisements. This particular link’s pitch states that if you got to school there, “you’ll be ready to turn your passion for design into something bigger than a hobby — a fulfilling career.”

These aren’t lies, I believe I can claim to be living proof. But they are exceptions. I seldom see other types of vocational schools, like Heating and Cooling Schools making the same pitch. In this example, the proposition is clear. There is no mention of passion and fulfillment. They spell it out straight away: you can get a job because this skill is in demand. And now, 10 years on, I don’t think I have had any more fun than anybody else at work, and I don’t think it has been any easier. Moreover, I recently met a guy who sells HVAC systems to nursing homes. He was way more passionate about what he does and the purpose he serves than a lot of graphic designers I know.

Compensation by any form other than money is the law of Diminishing returns

Once, while contracting artwork from an illustrator, I asked him at our first meeting, “How much will this cost?” “It depends,” he replied. “It depends on how much I like it.”

I will always remember that conversation. It was the first time the relationship between the enjoyment of a task and compensation for that task was brought fully into focus. What he said to me was this: The more I enjoy working with you, and the more I agree with the final outcome, the less I will charge you, because there is a real worth in enjoying what you do; a real cost in not enjoying it.

Since that conversation, I have held my own work up to that prism. The more I enjoy anything, the less perceived value it is to the paying public. Here is one way that it happens: fully exercising my love for photography in my personal life has devalued photography on the open market. The surplus of supply of in my personal life lowers its demand in my professional. If I really enjoy photographing with no apparent compensation so much as my Flickr stream demonstrates, then surely, -the logic has been presented to me many times – surely, I will enjoy photographing for someone else too. “I know how much you enjoy taking pictures,” they often say with a careful look, “I’d like you to photograph “X” for me, and I hope you’ll consider the experience (and the assumed flattery) as payment for your time.”

The difference seems obvious to me: I do get compensated for my personal work. It’s just not in a way anyone one else can understand. When people ask me to work for them for free “because I like doing it”, they do not understand that working for them, and by their schedule and needs inherently changes the nature of the work. Money is the only form of payment they are able to provide.

For years, these situations have been presented to me time and time again. To continue my example from my first correction, I’ll assume the example of an auto mechanic. Most auto mechanics enter into their profession because they love cars, or they love some tangential aspect of cars: engines, restoration, or the automotive industry. That is to say, they probably like their jobs as much and as often as I do. But I cannot imagine walking into my mechanic’s garage and proposing this: “I know you like cars, I’ve seen that great Mustang fast-back you have in your backyard. I see you always working on it. I can tell you spend a lot of time on it. Say, I have a bad water pump on my jeep. Because I know you like cars, would you replace my water pump for free? I hope you’ll consider the fun you’ll have replacing my water pump as payment from me.”

Of course this is not an appropriate thing to ask. In fact, it is disrespectful. One’s time may be the most valuable thing we have. That aside, the hard-earned experience of being a good mechanic is worth something. The tools and the maintenance of those tools is worth something. To ignore these things and to ask a mechanic or a photographer to do their work for free shows both ignorance and tactless self-interest.

The mistake is for the mechanic or the photographer to say yes to this. By saying yes, we take the immediate compensation of enjoyment and of a generous deed as the sole form of payment. (Not to mention, saying yes to free work undercuts other photographers and devalues the craft’s worth in the market for everyone). And any payment besides money is a diminishing return: the more you rely on intrinsic or non-monetary forms for compensation, the less they are worth you to.

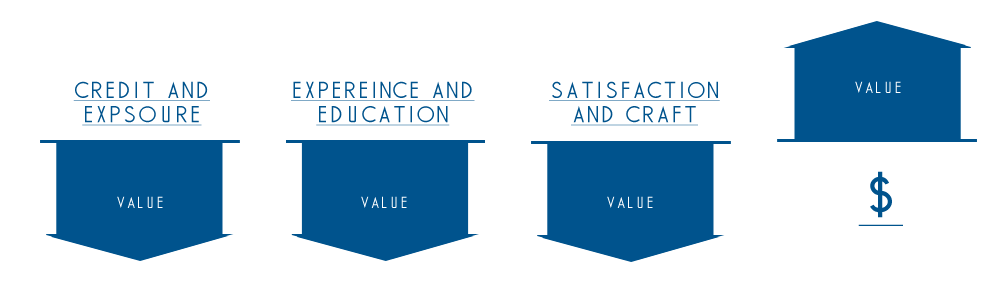

In my career, I can categorize compensation into the four following forms: 1. Credit and exposure 2. Experience and learning 3. Satisfaction in craft, and 4. Money or equivalent trade. All forms are necessary, especially the third. Satisfaction in doing your craft is the only form of compensation that is wholly internal. No one can give it to you, no one can take it way. But, like the first two forms, it is not sustainable in the long run, nor viable in the short. The more exposure you get the less you need it, and therefore the less valuable it is. The more experience you have, the less you need it. The satisfaction of a job well done to the best of your ability wanes over time when no external payment is received. Money is the only form of compensation that you don’t get tired of. In other words, I haven’t yet found a way to not need money. And why do I need either exposure or experience? The eventual answer is to increase my ability to earn money. To my younger self, all four forms would seem inherent to any work, without question. And all four were very valuable. Now, after 10 years of photo credits, some high-profile work, gallery exhibits, and pages upon pages of published photography and design, my ego is plenty satisfied. I have a new definition for professional success, and it is as simple as the first profession on earth. I perform my expert services for money. Eventually, we all arrive here because pride is good, but not as much as being hungry is bad.

It appears my means are different but my ends are not: I want to earn money for my work.

First, the means. Times are different. I need to think differently about what a career means and what I expect it to provide. Sitting around a campfire, my father might have summed it up best when he said, “I never hated my job. Some days were better than others, but I went to work everyday because it was my job.”

I can find happiness in lots of places. My job doesn’t need to be one of them. This basic principle has been hard to learn, because I have been taught to believe my job should be much more than a tolerable paycheck, and because the other currencies in the creative field are rewarding – at least for a while.

Second, the ends. I dislike spending money almost as much as I do making it, so while on the topic of jobs, I should take a moment to also critique my expectation of what money buys me.

Times are different. It’s not 1952 post-war America now. I don’t yearn for new frigid-air kitchen appliances to show off my prosperity, or the 55” flat panel T.V. that has taken their place today. Those things are made in China now and anybody can get them for cheap at Wal-Mart on credit, anyways. I don’t believe in finding a job that will support me in 40 years with a pension program. Those jobs are in China making kitchen appliances and televisions.

At best, this quest for financial health will afford a house that may or may not prove to ever be worth more than when I bought it, and some comfort and stability while living in it. (A 40″ T.V. will be fine.) This seems a fair and sober desire. In fact, it sounds a like a lot of my friends who profess to hate working in a cubicle everyday.

My point is this: Because my means for success – my job – seems fun, different, or unusually rewarding to some, it does not mean I don’t want what the next guy wants, so why should I, or anyone else, assume my compensation be any different?

When who you are is what you do, it gets hard to draw boundaries

The truth is, I do really enjoy what I do. I have made some pretty big sacrifices and had some pretty unbelievable adventures in the pursuit to be as best I can at my craft. I do this sort of work because I like to see, and learn, and report it to others in some way that makes sense of it. At its core, there is no difference between my personal work and my professional. Often the only difference is that sometimes other people pay to judge it and they get to call it their own when I am done.

Now there needs to be boundaries. There needs to be a withdrawal. I cannot share what I do with everyone. I cannot demonstrate my acts so freely. Giving away free samples only works at the grocery store. And I am not even sure that works. I’ve never bought anything from those free stands, I only expect more free samples, and I cannot expect others think any differently.

I cannot expect money to fully compensate passion. I cannot expect others to value my work as much as I do. Moreover, I cannot expect others to value my work when I love my work enough to do it for free. And I can’t argue with Confucius. By some standards, maybe I never will “work a day in my life.” But I need to love and work differently, and that will take some work.

One thought on “The Correction, Part 3”

Comments are closed.