The prevailing notions that have been the foundation the last ten years of my professional life are: #1 working for yourself is great, #2 that technology allows for telecommuting so that you can live in one locale and work in another, and that it will be easy, and #3 doing what you love will give you a happy life.

After ten visceral years of living this experience to my fullest capabilities, I have removed all the vague but powerful impulses that have led me down this road, and I am able to isolate and identify these grand assumptions. With many experiences behind me, I am now able to learn from my own history, and correct it so that I might better myself as I continue through life.

CORRECTION #2: Telecommuting Is Great.

I was raised during the 1990’s and entered the professional working world in the 2000’s. The unanimous sentiment among my educators, influencers, and peers was that the internet, and technology as a whole was going to radically change the way we work, and it would all be for the better. And better, nearly always meant more convenient, faster, and more immediate. The internet age was barreling around the bend, and we were all encouraged by those older than us to jump on. In hindsight, this seems akin to the tale of the tired farmer who encouraged their children to go to the city to find a better and easier life. But in a twist to this comparison, the most discussed conveniences touted to me as a young and eager designer was the new wonder of telecommuting, which allow us to stay on our version of the farm.

The internet, as it was explained to me, would allow me to be anywhere, and do my work online, and connect digitally to anywhere else in the country, even the world. I did not have to see or be physically in the presence of my co-workers or clients. I could stay on the proverbial farm, or anywhere I chose, perhaps where the cost of living was low, and I could perform and charge for services that were in demand elsewhere and possibly for higher rates than my local market could offer.

This notion of “stay here, work there” was happily pitched to me by people of all stripes, some who were unionized workers, whose bumper stickers on their domestic cars said “Buy American”. I guess they were a little slow to see globalization trickle down past them to and land in the laptop of an 18 year old kid. Today, the pendulum has swung back in interesting ways: the “buy local” movement has manifested in food conscious circles encouraging us to stay closer to home with our diets to improve our health and the health of our community. Now I see some people touting their locally eaten produce from the farmer’s market on Saturday while Skyping with their boss in Stuttgart on Monday.

I could explain more of my experience with these notions, but anyone today born in the first-world, in second-half of the 20th century is now familiar with the concept: the internet removes the need to be physically present. And today, we are all telecommuters, if not in our professional, lives, then certainly in our personal ones. The internet has encroached on every aspect of personal and professional human interaction. And somewhere along the way, we all seemed to think that was a great thing. Now, 10 years into my professional career, I have a correction on this idea to make for myself.

To do anything well, you need to use both hands.

On the internet, I split my physical and intellectual self, where one is, the other is not, and both suffer. This is what that means: wherever I am, my thoughts are required somewhere else. Where ever my thoughts and attentions are, I can not physically be. In this situation, neither experience is visceral, neither satisfying. The people in my physical surroundings are intellectually and emotionally ignored. The people in my digital surroundings are physically ignored.

When the receivers of my messages are not in my physical surrounding, I am not in context with who I am trying to reach. I cannot read the cues of timing, expression, body language, and syntax to even communicate common pleasantries, let alone creatively complex concepts. I can’t cater my ideas and my message to my clients; I am only connected to my audience in blind bursts of rudimentary text. In other words, there is no more ‘art’ to communication. As a visual communicator (let alone a human being) this form of discourse takes away half of the composition required for successful and meaningful work.

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the increasingly ubiquitous nature of communication. When the internet flew the coop of the desktop computer and took flight in our laptops, we could work at the coffee shop. When it leapt to our mobile phones, we could work while walking our dogs, while in bed with our spouses, while having dinner with our families, while driving on the highway. And as with most of human history, we are more interested in measuring progress by asking, “I bet we can.”, not “Why should we?”. This new life leaves my physical self often unattended at any time of the day or night, emotionally and intellectually disconnected and unaware, and messages off all matter and priority are funneled into the same medium directly into my pocket, more convenient, faster, more immediately then we had ever envisioned. (See Example.)

In some aspects, this flood of accessibility to personal technology has had the same affect as any other resource that becomes abundantly available. With more an cheaper food, obesity rates rise. With more and cheaper guns, deaths rise. With more an cheaper cars, traffic and accidents rise. For the most part, it seems to me that as a whole, we are not incredibly good at rationing anything. We grasp for it, gorge on it, and try to deal with the affects later. For myself, I am trying to deal with affects of communication technology now, starting with my professional life.

Convenience for Quality? What a deal. I’ll take two.

Communication is becoming ever convenient. There are many things to celebrate with each advance. However, with every increase in convenience we always trade it for a lessening of quality. It began when we started writing letters. It was no longer conversation but a monologue. Then came telephones, telegraphs, emails, instant messages, text messages, Facebook posts, tweets, retweets, pokes, and ‘Likes’. With each mode of communication, more convenient than the last, we continually sacrifice what it means to communicate meaning and sense.

As it gets easier to ‘communicate’ the volume of messages coming to us increases, and we (at least I) cannot give each the effort they deserve. Our responses get reduced, and immediate sending expects immediate replies. We are talking when we should address the clerk at the coffee shop and give them the acknowledgment they deserve, and the money we owe them. We need to pick up the dog shit. We need to enter the highway at 5:00, we need listen to the woman we love. We need to pay attention here and now.

Sherry Turkle, author of Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, stated in an interview on NPR:

… another thing that’s happening is that when you start to get that many emails, when people start to get at mad you if you’re not immediately responding to them, you start to ask people questions that you know they can answer quickly, but you start to ask simpler questions. We start to give simpler answers. You kind of dumb down the questions. You dumb down the answers. We kind of all put each other on cable news. I mean, we say that our world is ever more complicated, but we’re asking and answering simpler questions. … (Read More.)

How this affects my work

How does all this affect me? Sure I can sit in armchair and complain about the humanist qualities we loose in today’s conventions, but I would be relegated as a luddite, a disgruntled complainer. But even if I put aside my personal ideas, the quality of my work, and therefore my livelihood are still affected in adverse ways. First, what is my livelihood? I am a graphic, or visual designer. I make my living by telling other people’s stories. I get paid to understand, distill, organize, and present other peoples ideas to their audience in a manner that has emotional, intellectual, and human resonance. I get paid to present information and ideas in the most readable, memorable and factually and emotionally accurate ways I can conjure.

With the ways of communication and interaction changing so fundamentally, I have my work cut out for me. Not only in the product I offer, but also in my process. By telecommuting, my ability to connect with my clients – to be able to understand their needs, and tendencies, to present my solutions to them and predict and adapt to their reactions – is drastically changed. When receiving my training as a graphic designer, great amounts of time and attention were devoted to “presentation skills”.

In college, 10 years ago as a student, and in even 5 years ago as a professor, curriculums required pupils to buy black presentation boards, print, and mount our ideas for the boardroom reveal. To make slideshows, to cater to our clients and their personalties, insecurities, and abilities. We were taught the importance of presenting our work, and receiving feedback, taking cues form the physical appearance, mannerisms, and reaction of our clients, in short, communications not just text on a screen. These where the ways to communicate our work; these were the ways to understand and to explain and to defend our work. This was how good work and good problems were solved in this discipline.

Now consider this. Today, almost none of my clients are within 60 miles of me. More telling, the ones that are just miles away, can never find the time to meet with me; They email me instead, at whatever times are convenient for them, and the respond to my emails at whatever time is convenient for them. This essentially reduces the pace and vigor of any conversation to the equivalent playing ping pong in a vat of molasses. We take turns serving rudiment textual projectiles slowly back and forth, a conversation that would take 5 minutes in person takes three weeks via email.

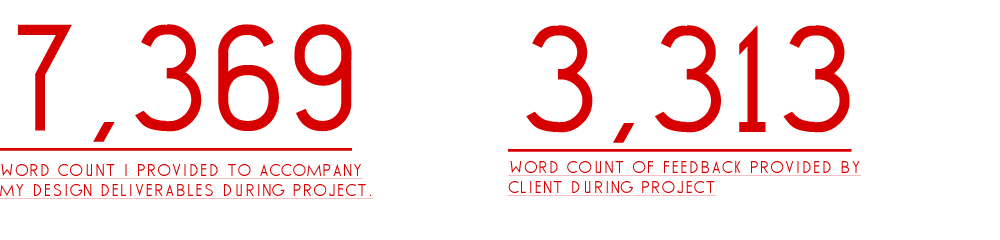

The following is a word count from the dialogue that transpired during a 2 month contract with a client I was commissioned to create web page designs for. I use a software called Basecamp, an online project management tools for communicating, sharing files and facilitating feedback. This is one objective way I try to understand the increasingly diminished satisfaction I get not only from the work I produce, but more importantly, the dismay at it’s process.

The comparison is made more unequal when I consider the PDF documents of research reporting, and almost 60 screen designs I submitted to the client via Basecamp. Does this discrepancy mean that my work is so good it needs no comment? Of course not. Even the best work elicits responses and commentary for improvement or consideration. And good work should elicit some positive response, bad work perhaps more. So often now as a dyed in the wool telecommuter, I have no idea if the work I am doing for a client is either pleasing or poor. Does this mean that my client was uninterested or not giving the attention deserved? Of course not; they were giving it the same amount of time they give all the correspondence coming into their inbox every hour of the day.

When proposing concepts and work, when requesting feedback, or requesting payment, it gets filed into an inbox somewhere else, right along with personal about weekend plans, Cialis pills or male enhancement, foursquare notifications, and calendar reminders for dentist appointments. Can I blame them for not responding in a timely manner? And when they do, at 8:30 pm on Saturday night, can I expect complete and punctuated sentences? Who knows how many other emails they need to tend to, or instant messages needed responses. For all I know they were walking their dog, eating dinner, or in the presence of friends when they submitted their feedback. How can I best craft someone else’s story if they can’t even effectively share it with me?

This is a correction I am making for myself. Telecommuting is easier, but is not better. We have not yet found a way to adapt to communicating effectively online. And with every advance in the medium, the message gets reduced. (Marshall McLuhan, you must be nodding somewhere.) It drastically alters my personal relationships and my professional process. It is not all bad, but often I am left to think the improvements we make in design are improvements to the medium, when I should be finding better ways to improve the message – we are trying to solve problems we have made by our own devices, and not improving what is being said in the first place.

I realize I am in the minority. Whether that is a strength or a weakness in my line of work is yet to be determined. Most everyone I speak with embraces the ways in which we communicate today, or are envious of those that do. Consider the American Telecommuting Associations list of “What’s So Good About Telecommuting?” Their list is long, and it is easy to believe. As I read this list, I am reminded that ideas are often only expressed in qualitative terms. The list touts the extra time Mommy and Daddy have at home. This is time, I have found, which has little quality to it, for me, my clients, or the people in my presence.

The problem is left for me to solve, to adapt to, understand, and correct for me and the people close to me, and not so close to me.