In 1918 on a 600 acre a farm in Edmond Kansas, Claud Conkey was born. About six years later in that same farmhouse, Claire’s Great Grandmother’s oldest brother had another son on that same farm, and called him Lester.

At that same farmhouse last week, Claire and I drove up the dirt lane. Claud was sitting on his four-wheeler under a shade tree by the garden. He didn’t hear us pull up to the house. We didn’t expect he would. He can’t hear, and we were advised to bring a pad of paper to write out communication with him. So with pen and paper in hand, Claire walked across the yard to meet her ancestors.

I may be biased, but I can’t imagine Claud sees too many girls like Claire just appear standing beside him around Edmond Kansas, but he didn’t seemed to be surprised, sitting quietly in his overalls. “You caught me sitting here didn’t you?” said with a smile before Claire could make her introductions by way of the white pad of paper.

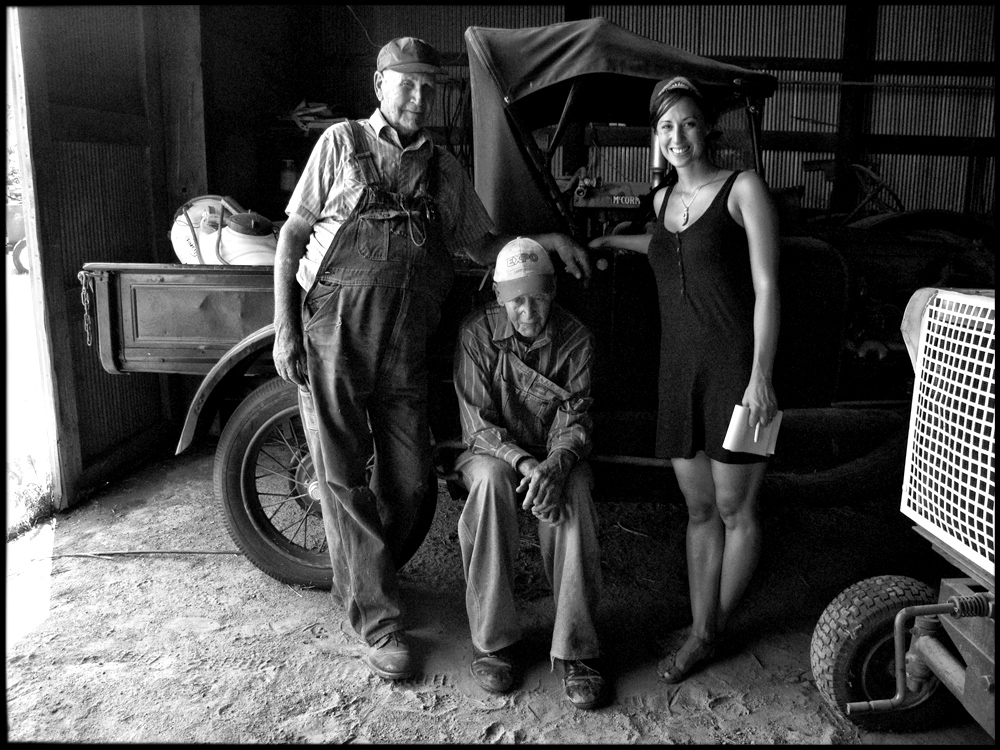

“My brother’s around here somewhere, mowing the grass.” Claud told us. “Come on, you want to see our cars?” His hands were bent into nearly permanent cusps, as if he were always holding a tool in them. Both his body and his mind seemed to have fashioned themselves to be suitable implements for his home – we were about to find out that these two brothers, who had lived in the same house their entire lives, were one of-a-kind mechanics, inventors, and collectors. He started his four wheeler and we followed him across the farm yard to the largest of several out buildings. His brother Lester approached – a tall, stately man in nearly an identical wardrobe of exquisitely worn overalls and black shoes and a seed company ball cap. Claire again produced the paper and pen and made introductions.

Lester is the type of guy who smiles when things are right, and smiles when they are not. With equal parts excitement and nonchalance bordering on sheepishness, he and his brother showed us around their farm. The first show piece was a 1935 Model A car body they drug home from a neighbor’s house and rebuilt as a farm jeep with two perpendicularly mounted leaf springs below the frame that ran alongside each axle. “We use it to pull the crop sprayer.” Claud added from his four wheeler. I imagine when you have lived over 90% of an entire century, time must surely have a way of compressing on itself like the sedentary limestone bedrock below our feet. So with each anecdote, I had no way of knowing what era their stories came from. I soon realized any of these stories could have spanned from last month to a time before our present map of the solar system was even complete.

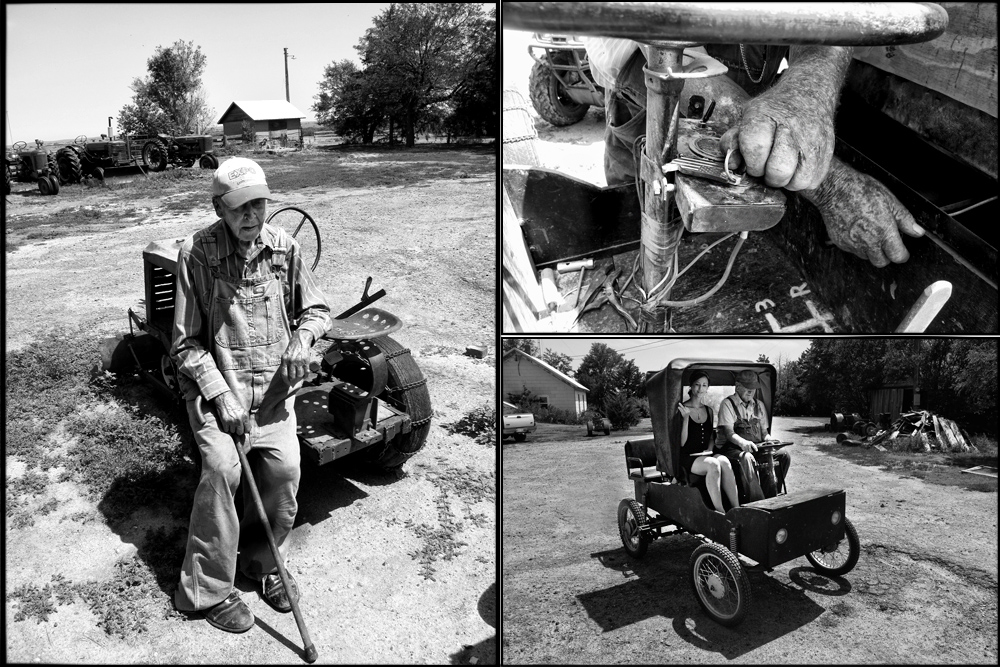

“Go on, give it a drive.” Lester offered. But the car wouldn’t start. So with a smile, Lester took out his bone handled pocket knife and unfolded the hood of the Model A. He wiggled loose the positive terminal of the battery and scraped the metal stud until it shown bright and metallic. A thread of smoke and sparks scattered from his pocket-blade. He was still smiling when he turned the key again and pulled out the long choke knob. As the engine turned over, we suddenly learned why these brothers were hard of hearing. The 2 inch straight pipe that rose vertically out of the motor, trimmed jagged and short with tin snips, screamed with smoke, less than 24″ away from the fire inside the archaic pistons.

As we continued the tour around the farm, it was evident that we were being shown the secret living museum of minor mechanical geniuses. I lost count after nine 1930’s era Ford, Chevrolet and International Harvester farm trucks. All in good physical condition, and I had no doubt, that might there be any mechanical maladies, they could have been easily remedied on this farm. There were well over a dozen tractors, all from before the first moon walk. Some sat like sleeping iron dinosaurs in the back sections of barns, others where bright and shiny and parked in the yard, for the hope of future visitors, or for plain and honest dignity, as if their invisible drivers were watching the Kansas sky like a drama on a drive-in movie screen.

One vehicle had pairs of tires wrapped in larger tires treads like tank tracks to drive in snow. Some looked like mechanical Frankensteins that oscillated in the middle. Some defied definition and classification entirely. They were pull started, ignition started, crank started, and some just required Lester’s fingers to poke down through butterfly valves deep into carburetors while the other hand tightened spark plugs. They bounced, wobbled and rolled along, with their pulleys and springs spinning and exposed like the innards of hunter’s whitetail deer gutted and spread, but still trying to run away.

In one barn, leather saddles hung like dried cocoons above metal sleds full of Massey Ferguson motors corralled like sheep in a stable. “Careful.” Claud said to Lester as he slid open the door, “Make sure one doesn’t get loose.” It dawned on me that I was experiencing riders who have rode almost the entire living timeline of history since the tail end of the Industrial Revolution; brothers who saw first-hand as young men the proliferation of the internal combustion engine, mass production, and the advent of domestic electricity use. As teenagers, they leapt onto new automobiles with similar wonder and excitement as I leapt onto the internet and cell phones when I was their age. They have first-hand knowledge that dates uninterrupted back to the dawn of the passenger car and the advent of modern farming techniques. I doubt if few people today know their craft so thoroughly and entirely as Claud and Lester. Few people have experienced as much innovation, adaptation, and utter revolution in technology and society as these brothers have, and they had seen it all from the same porch stoop just outside Edmond Kansas.

An often agreed upon definition of an ‘expert’ in academic circles is someone who spends 10,000 hours at their trade. At 8 hour work days, these two men have a combined experience of 152 adult years (starting at age 15), or an approximated 425,600 hours of hands-on-experience, given an 8 hour work day. With a pen and paper I wrote down: “How did you learn to do all of this?” and showed it to each.

Their answers where nearly identical. Each replied, with a strong sense of amusement and deference: “Oh all of this? Ah, no way really, just by working at it, I suppose.”

As I leaned against a homemade tractor in the bright sun just outside Edmond Kansas and watched Claire be given a ride around the farm yard in a home-made motorized horse carriage on motorcycle wheels, I said to Claud, “Then I must really have a lot of work ahead of me.”

He didn’t hear me. But I wasn’t saying anything he hadn’t already found out for himself.